Mike Davis at Lovecraft eZine asked me to run an adventure for their Google+ Hangout-fueled Call of Cthulhu games, and naturally I jumped at the chance. The first game was Friday, December 13, 2013, and Mike was especially interested in something that evoked the ice and mystery of “At the Mountains of Madness.”

I looked to the North Pole for an adventure that I love but which is hard to find: “Dead of Winter,” the prologue scenario in John H. Crowe’s epic campaign Walker in the Wastes. It’s about as wintry as you can get, with Investigators trekking across the snow and ice, and it works great as a stand-alone adventure.

On a personal note, I was thrilled to get a chance to run it. I corresponded with Pagan and fellow fans about it back when it first came out in 1994. I even got a little envelope of clippings and art as handouts from Pagan House before they published the official Walker in the Wastes Keeper’s Kit. After all that, this is my first time running “Dead of Winter.”

Part 1 of 3

Here’s Part 1, from December 13, 2013:

Part 2 of 3

From December 20, 2013:

Part 3 of 3

From December 27, 2013:

Full Playlist

The Investigators

- Dr. David Dillsworthy (archaeologist)

- Dr. Jack London (archaeologist)

- Dr. Victor Lustig (anthropologist)

- Dr. Christopher Hamilton (geologist)

- Dr. Alan Scovill (botanist)

- Dr. Jason Decker (zoologist)

- Dr. Cornelius Brand (physician)

- David Horning (handyman)

- “Charlie” (Poo-Yet-Tah, Inuit guide): NPC

Game Resources

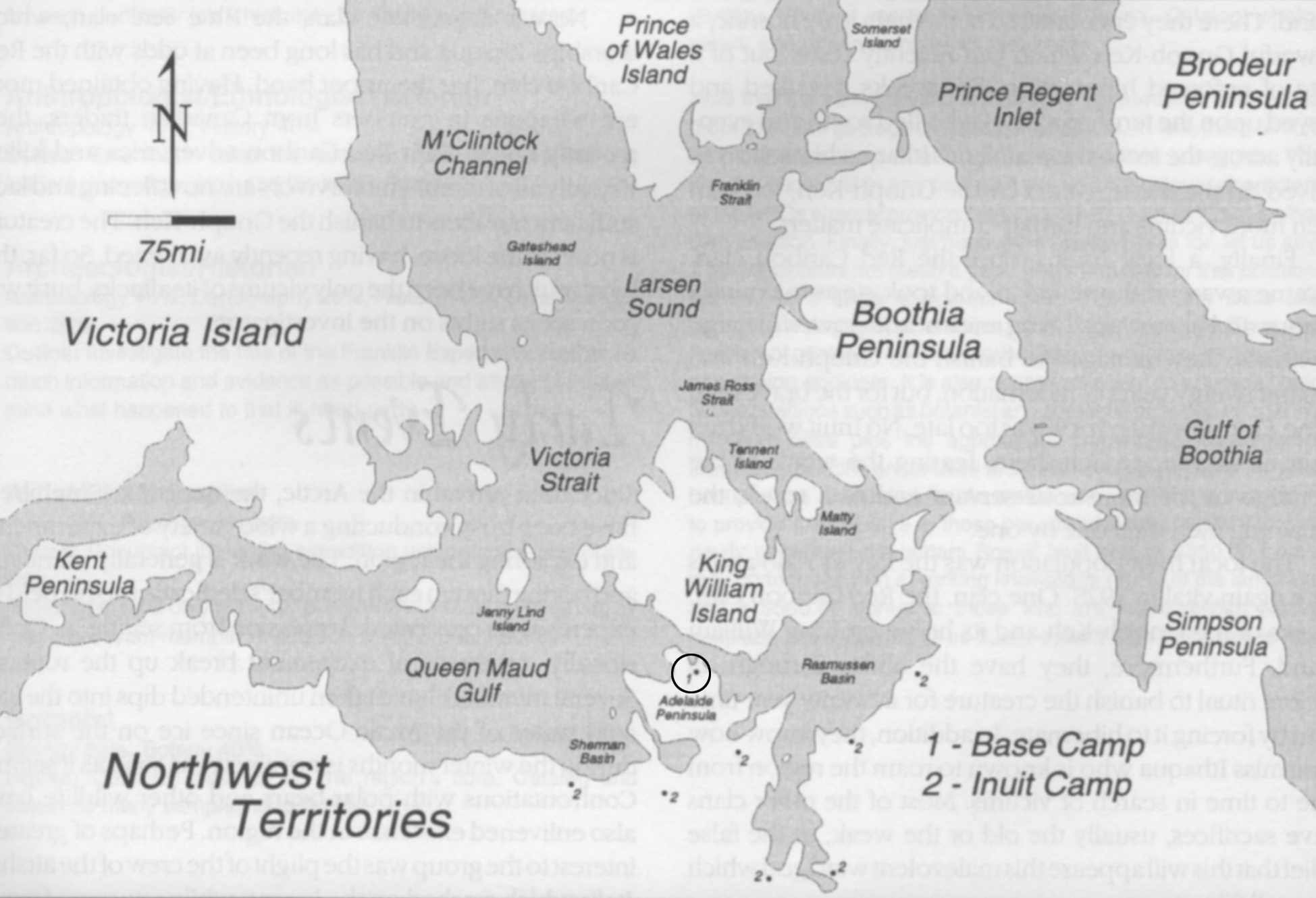

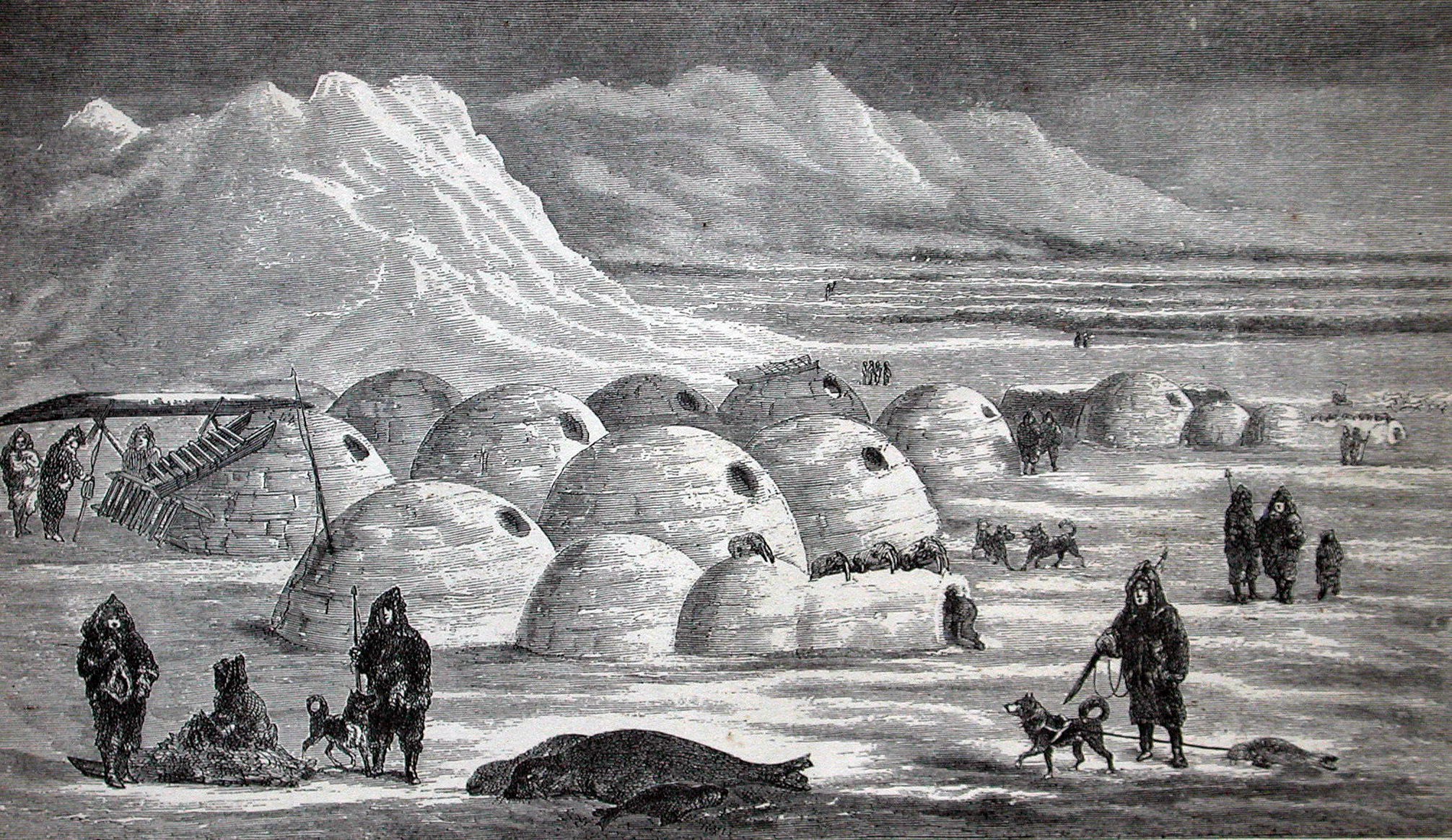

“Dead of Winter” opens with scientists in a long-term Arctic study in 1928. To prepare for the game I did a good bit of reading — Walker in the Wastes is filled with great resources but I like to be thorough — and found some nice art to set the scene. I also scanned a few maps from Walker, which are © 1994 Tynes Cowan Corporation, and from my own Funk and Wagnalls 1923 Atlas of the World and Gazeteer.

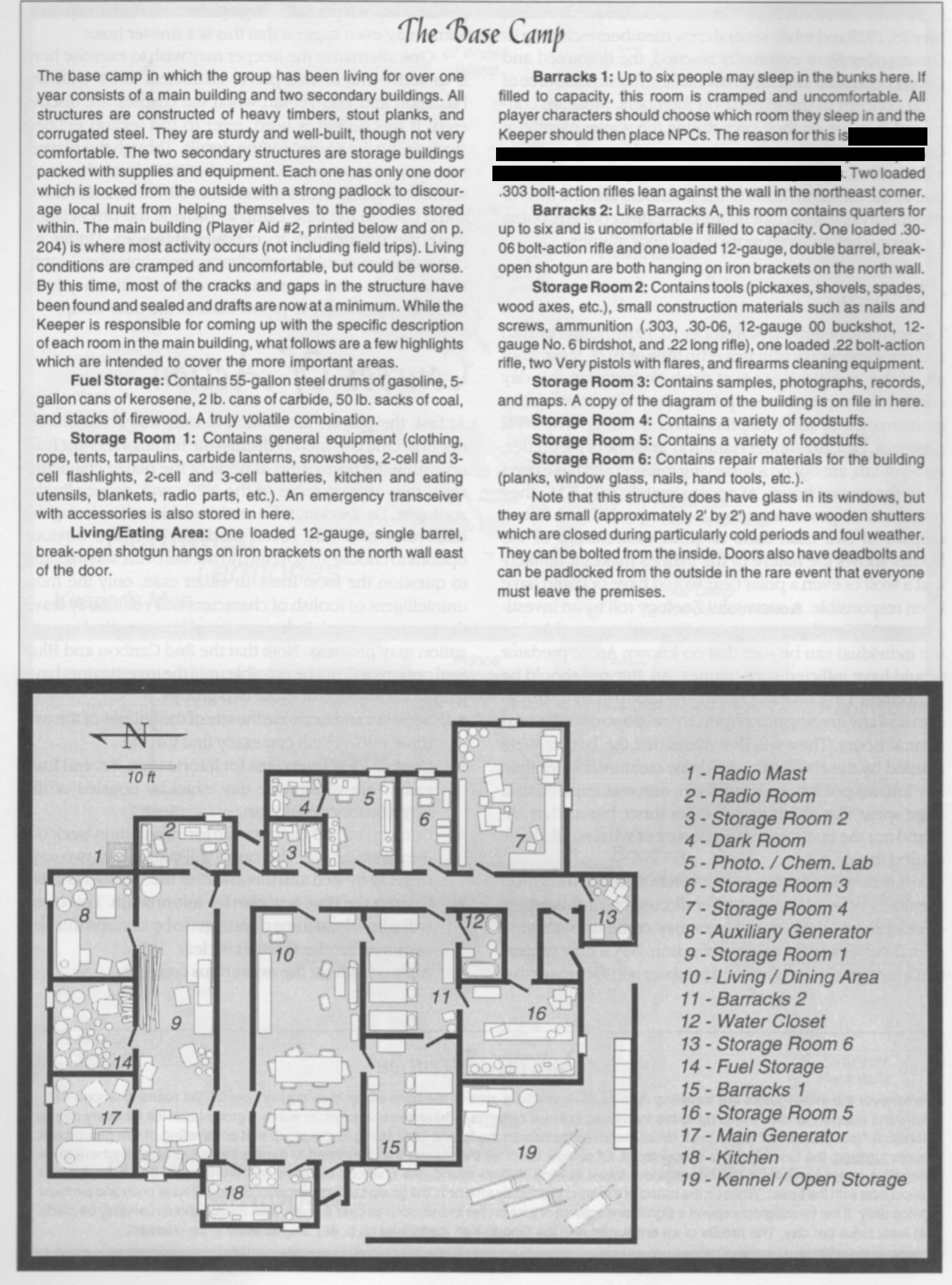

The expedition’s base camp. From Walker in the Wastes, © 1994 John H. Crowe III and Tynes Cowan Corp.

A sample of the architecture of the base camp. The team’s base is a bigger, sprawling, uneven building.

Introduction

Adapted from Walker in the Wastes, © 1994 John H. Crowe III.

In May of 1845, the Royal Navy vessels H.M.S. Erebus and H.M.S. Terror quietly departed their harbor in the Shetland Islands. Commanded by Sir John Franklin, they sailed on a quest to discover and chart the long-sought Northwest Passage. They were big, strong vessels with provisions for seven years. They were seen in July of 1845 off Greenland—and were never seen or heard from again.

Search parties set out starting in 1848, but they have never found the Erebus and the Terror—only bones and artifacts that the sailors left behind as they tried to escape, and tales passed down in Inuit tribes of the great ships stuck in the ice.

At first, the searchers slowly learned, the Franklin expedition made excellent progress. But this ended when the Erebus and Terror were beset by ice north of King William Island on September 12, 1846. On April 5, 1848, the doomed vessels were abandoned and the remaining crew members made a futile attempt to march south to safety at trading posts in Canada. Unfortunately, their trek failed and all succumbed to starvation, disease, and the elements.

Your investigators are part of a long-term expedition to the northern reaches of Canada. Sponsored by the University of Toronto and the Canadian government, the plan is for a select group of experts and scientists to live and work in a permanent base camp on the Adelaide Peninsula, near the location of the remains of some of the Franklin Expedition members. Your aim is to study life in the Arctic and search for the final resting places of Erebus and Terror.

The expedition left Toronto on June 10, 1927 and will return on June 14, 1929. It is now November 10, 1928. For a year and a half, the team has lived in the Arctic. In the summer it’s dead rock and water. For the rest of the year, the world from horizon to horizon is ice.

The last report of the Franklin Expedition, found in a lifeboat along with the bodies of some of Franklin’s men.

“Man Proposes, God Disposes,” Edwin Henry Landseer’s interpretation of the fate of the Franklin Expedition.